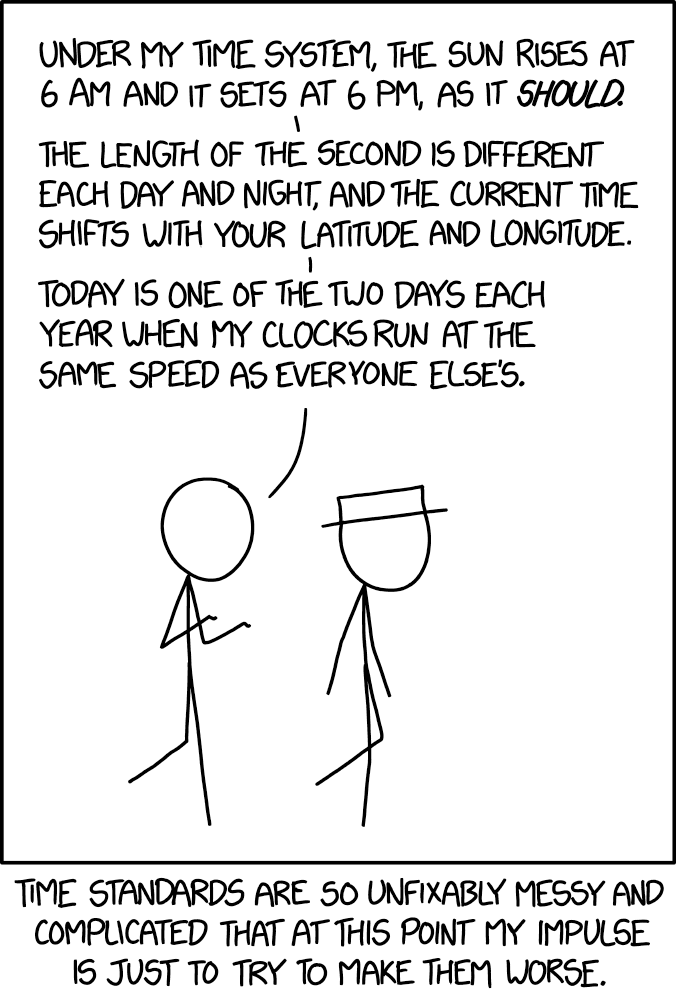

Note 3: Time dilation and saving the Right to the Future Tense

Notes on the variable passage of time and a weird amount of antitrust discussion.

In Note 1, I wrote about how we are all traveling at lightspeed through spacetime. Implicit in that discussion was that our speed through time can be just as variable as our speed through space. It’s a neat property of our reality, and a fun metaphor for how we experience the passage of time.

I’m not going to dig into the science and philosophy of variable time perception, but I wanted to use it as a jumping off point for how weird 2020 has been on that front. As you read this Note, we’re already past the half-way point in the month of September. I don’t know about you, but I simultaneously feel like it was both a hard slog to get to this point, as well as a sprint that surprises me that we’re here already. For me, my experience of the passage of time seems to be a function of creating temporal landmarks. If something happens that’s significant and different from my daily life, that landmark becomes an anchor for events that happen around it. If nothing significant happens around these events, they remain unanchored and end up forgotten or difficult to recall in the future. Unrecalled time is “fast time”, so the monotony of life in COVIDtide both feels tedious and slow, while also being immediate and almost too quick to fully appreciate.

I wonder if this experience is unique to me, or something other adults also experience. I also wonder if the experience is different for parents - I have a theory that children’s landmarks are incorporated into their parents’ temporal landscapes, and the passage of five years for a parent is fundamentally different than the passage of five years for adults without Mini-Mes to herd and manage. If any parents reading this wish to comment, I’d love to hear about your experience on this front.

How to Destroy Surveillance Capitalism

One of my personal temporal landmarks - like everyone else alive in America at that time - was the 9/11 terrorist attacks. I was about start my senior year at Princeton, which included plans to visit the World Trade Center before the scholastic year got too busy to think about trips to The City. Needless to say, I never got around to that trip in time.

2001 was also landmark year in that it was also the year that my first work in context-aware computing started with a software framework that I was writing for my senior thesis called “GeoServer”. The idea behind GeoServer was that it was a neutral platform for collecting location information from people and devices out in the real world, and that data could be queried, aggregated, and displayed in a variety of ways that would provide additional value that the original providers the original data couldn’t anticipate. To demonstrate the platform, I built a number of demonstration applications: a three-dimensional map generator (when I have a chance, I have some fun 3-D maps of Capulin Volcano in New Mexico and Five Blues Lake in Belize to share), an app for a friend that would allow amateur mycophiles (mushroom enthusiasts) to record and share finds, and a proof-of-concept live location tracker assembled out of a Garmin hardware GPS connected to a Compaq iPaq that transmitted location updates through a 3350 Nokia phone.

Since my work on the initial GeoServer platform in 2001, I’ve spent most of my career at this point working on the problem of how to collect telemetry data from both the physical and virtual worlds, and how to put that data to good use. I’ve almost exclusively worked with academic researchers on this, primarily in the field of behavioral monitoring and changes. GeoServer begat Pennyworth, which begat Purple Robot (by way of Mobilyze), which begat Passive Data Kit.

Last year, Shoshana Zuboff released her book, The Age of Surveillance Capitalism: The Fight for a Human Future at the New Frontier of Power. In her exhaustive take on the modern ubiquitous data collection, data mining, and behavioral modification that permeates our modern world, she discusses how surveillance capitalists take advantage of the behavioral surplus generated by users and consumers to subtly (and sometimes overtly) modify interactions with information environments to nudge people into specific monetizable actions, depriving people of their right to the future tense. The book is exhaustive in its thoroughness, and it was a long relentless read for me, as she painstakingly details to what extent our world is infested with these mechanisms, and what it portends for our future.

I’ve been saturated in this world for most of two decades on the technical side, and it was still an eye-opener for me:

The third section of Zuboff’s book is dedicated to describing a new ideology—instrumentarianism—that she says will dominate the 21st century. To explain this new species of power, she returns first to the midcentury work of the psychologist B.F. Skinner, who argued that free will was an illusion and that any action that seemed freely chosen or spontaneous was just a behavior that had yet to be predicted, explained, and conditioned by behavioral psychology. Eventually, Skinner posited, such analysis could be used to replace the chaos of individual “freedom” with large-scale social engineering. This idea, Zuboff argues, has now been taken up by leading researchers like MIT’s Alex “Sandy” Pentland, whose 2014 article “The Death of Individuality” suggests that we ought to do away with the individual as the governing unit of rationality and focus on how our society is governed by a “collective intelligence.” Although most Silicon Valley developers seem to lack Skinner’s and Pentland’s utopian (or, rather, dystopian) ambitions, Zuboff warns that their quest to profit from behavior modification will eventually merge with instrumentarianism’s project of social control.

(From The Nation’s review: None of Your Business: The rise of surveillance capitalism.)

Before COVID struck, I finished reading the book and was debating what my role in all of this was and whether my two-decade project in telemetry platforms was something that I could morally justify continuing. In contrast to the folks mentioned in Zuboff’s book, the overriding ethos of my own work has been collecting data and putting that data to use (using the same techniques and methods as folks like Pentland) to productive ends primarily in the area of physical and mental health. (Disclaimer: A handful of my own clients and past academic collaborators are mentioned by name - in various moral capacities - in Zuboff’s volume.) I have a general optimism with respect to humanity and the design and implementation of my platforms like Passive Data Kit has always included embedded within it mechanisms for giving true informed consent by not only educating users upfront what an app will be collecting, but also providing interfaces and mechanisms for users to visualize and review the data themselves that we’re collecting, as well as mechanisms for being to request copies of their own data for their own use. My belief is that one reason why digital surveillance is a problem is because keeping users informed is not a trivial matter. To what extent I can build tools that make doing the right thing cheap and easy, I can help developers and their companies be more responsible actors in our society.

I was gung-ho to figure out what my role in all of this - whether to continue, advocate, etc. - then COVID struck, sucking all the oxygen out of the room. My attention was quickly devoured by my research clients seeking to redirect the existing surveillance research platforms we had out in the world toward studying COVID, and I’ve been running around since March like a headless chicken trying to keep up. I also saw a major uptick in my SMS and dialog engine business at that time. Until recently, figuring out how to modify or destroy my own technology to prevent the Instrumentarian Takeover was placed on the back burner.

I returned to the topic last week after reading Cory Doctorow’s new book How to Destroy Surveillance Capitalism, a response to Zuboff’s narrative that leverages Doctorow’s experience as a digital activist to deal with the problems that Zuboff identified:

Surveillance capitalism challenges democratic norms and departs in key ways from the centuries-long evolution of market capitalism.” It is a new and deadly form of capitalism, a “rogue capitalism,” and our lack of understanding of its unique capabilities and dangers represents an existential, species-wide threat. She’s right that capitalism today threatens our species, and she’s right that tech poses unique challenges to our species and civilization, but she’s really wrong about how tech is different and why it threatens our species.

What’s more, I think that her incorrect diagnosis will lead us down a path that ends up making Big Tech stronger, not weaker. We need to take down Big Tech, and to do that, we need to start by correctly identifying the problem.

Doctorow’s book is largely a response to Zuboff’s lack of suggestions for how to effectively respond to (what she calls) Big Other. While Zuboff nails the description of the dangers we face, like a lot of academic writers, her solutions are a bit light and under-developed:

- Additional legislation and tough enforcement of laws like the European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). The GDPR establishes a number of important rights for Europeans, including the right to know what personal data an entity has collected about you, the right to receive a copy of all the personal data from an entity, to whom the entity has disclosed your personal information, and a right to correct or delete the data that the entity holds. The US already has a law similar to the GDPR on the books - the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA) - but it’s limited to the types of data protected (health) as well as the entities subject to the HIPAA’s jurisdiction (covered entities and business associates).

- An expansion of the Fourth Amendment of the US Constitution to other private parties.

- Data sabotage and systems for evading detection and data collection (a topic I discuss very briefly in my Masters thesis). A good historical example of this is Dazzle camouflage, which is making a comeback (in spirit) both in physical and online environments.

- New personal networking technologies that eschew the cloud-centric architectures that wearable device firms use now, in favor of data being aggregated on a device on the wearer’s person.

- Good old-fashioned public outrage and exposure.

Doctorow, drawing on his history as an online and privacy activist, ends up being a bit less fatalistic than Zuboff and highlights that there is value in services that aggregate and process personal data, and the issue to address isn’t responding to the onslaught of instrumentarian capitalists, but instead to keep the surveillance firms from growing too large to manage and regulate effectively. Doctorow points to concrete policies that could be enacted now, such as expanding and enforcing data portability requirements (as the GDPR and HIPAA already do) - which would eliminate the advantage of incumbents’ network effects by allowing users to move their data and content to new competitive networks - as well as a renewed commitment to robust enforcement of anti-trust law.

Doctorow’s anti-trust discussion is probably the strongest part of his book, where he argues that we need to undo the modern interpretation of anti-trust regulation, which came about during the Reagan administration, when Reagan appointed Robert Bork to the U.S. Court of Appeals. Bork’s reformulation of anti-trust regulation de-emphasized regulating monopolies on the basis of power, but instead as a mechanism for reducing “consumer harm”, as expressed in higher prices. There may have been some merit to Bork’s reformulation in the 1980s (I’ll leave that to the Bork fans to discuss), but it’s clear that an anti-trust policy that only sees price as a signal for when something is going off the rails will be completely blind in a world where services are free and operations are monetized via the capture of behavioral surplus. Doctorow argues that we need to return to the original understanding behind the Sherman Anti-Trust Act that views firms as achieving dominant control of markets and consumers as entities that should viewed under heightened scrutiny and suspicion, and regulated accordingly. The Sherman view is the antithesis of “too big to fail” that we continue to tolerate in our modern economy.

Despite calling for more robust regulation, Doctorow fundamentally remains a capitalist at heart, arguing that if we didn’t allow firms to grow past a threshold that discourages competition (he calls these parts of the market “kill zones”), we can align incentives in a manner that limits the damage any single firm can cause through malevolence, selfishness, or negligence. In Doctorow’s formulation, the problem isn’t in the data collection, it’s in the large scope and size of the entities doing the data collection.

Doctorow’s book is a quick and clear read that I’d recommend to anyone - he summarizes the problems that Zubloff identifies quite well, so you can skip Zuboff if you’d like - and his approach is one that doesn’t throw the baby out with the bathwater, and he acknowledges that there’s still some good that can be done using the same techniques and methods that surveillance capitalists have co-opted in order to try and monetize each of our own Future Tenses.

Postscript

As I was writing this note, a very interesting whistleblower memo leaked out of Facebook from one of their data scientists who worked full time trying to protect the platform from malevolent actors:

Facebook ignored or was slow to act on evidence that fake accounts on its platform have been undermining elections and political affairs around the world, according to an explosive memo sent by a recently fired Facebook employee and obtained by BuzzFeed News.

The 6,600-word memo, written by former Facebook data scientist Sophie Zhang, is filled with concrete examples of heads of government and political parties in Azerbaijan and Honduras using fake accounts or misrepresenting themselves to sway public opinion. In countries including India, Ukraine, Spain, Brazil, Bolivia, and Ecuador, she found evidence of coordinated campaigns of varying sizes to boost or hinder political candidates or outcomes, though she did not always conclude who was behind them.

“In the three years I’ve spent at Facebook, I’ve found multiple blatant attempts by foreign national governments to abuse our platform on vast scales to mislead their own citizenry, and caused international news on multiple occasions,” wrote Zhang, who declined to talk to BuzzFeed News. Her LinkedIn profile said she “worked as the data scientist for the Facebook Site Integrity fake engagement team” and dealt with “bots influencing elections and the like.”

It’s well worth a read and is important to remind us that we not only need to be on-guard against competent capitalists attempting to monetize our Future Tenses, but also that the machines that these capitalists are creating can and do exceed their ability to control.

If there’s anything that drives home Doctorow’s message that these platforms have gotten too large, malevolent state actors overwhelming them to obtain nation-scale outcomes is one of many contained in this leak.

Local updates

The last week was wet as the summer heat gave way to autumn cool, and all that evaporated moisture came back down as a drizzly rain. This was great for my grass-growing project and I was very pleased to see mushrooms sprouting in the yard.

The presence of the fungi shows how much moisture the soil is absorbing, and the ‘shrooms are hard at work breaking down the cellulose and lignin from a decade’s worth of mulching, dead tree roots, and other items in the soil that have locked up nutrients that my grass and other plants would appreciate.

In Non-Intuitive News this week, I was able to solve a problem that’s been vexing me for months. As my prior Note indicates, I’m still a fan of traditional pay-TV and I’ve had issues since May with my signal dropping out and making cable television almost unwatchable. It became worse when I replaced the cable modem to get higher speeds and this has been driving me nuts.

I replaced the cables, the splitters, and all of the infrastructure I could get my hands on, and arrived at the conclusion that the issue was the modem. The picture was great when it was disconnected, and went to crap once I wired it back up. While on-hold with Comcast over the weekend, I did some research (learning more about how cable Internet works than I ever wanted) and came across a novel solution: Instead of improving the signal to the television, what if I made it worse?

The theory was that the the television was less sensitive to a weaker signal than the cable modem and by weakening the signal to the TV, I could overcome the modem’s interference and get my picture quality back. I found out that I could replicate the interference reliably when doing a massive data upload (such as a bunch of DC Comics covers to Fresh Comics, see below). So I took all the crappy splitters and cables that I replaced over the past couple of weeks and inserted them into the path between the cable coming into the house and the television, leaving the modem’s path unimpeded. Television signal predictably went down and picture quality improved!

Now there’s no interference that I’ve seen since then (and I’ve been unable to replicate the problem), and the fix is just in time for my New Favorite Thing.

As folks who know me will attest, I’m a big weird horror fan. I cut my teeth on Lovecraftian cosmic horror, but have switched gears in the last few years to the British folk horror subgenre. This last Monday, HBO debuted the first episode of their new miniseries The Third Day.

The trailer for the show gives of some very intense Wicker Man vibes, and I’m on-board for that. However, this being HBO, I’m very interested to see to what extent the series veers from the predictable folk horror tropes and does something innovative and interesting with the genre, not unlike what they did with the first season of True Detective and early Chambersesque weird fiction tropes. I’ve only seen the first episode do far and am still in the “setting the stage” part of the story, but the series is worth viewing on its own, if only for stunning cinematography and audio production.

Getting back to temporal landmarks discussed above, I expect that the Monday airings of The Third Day will end up how I mark the time for the next six or seven weeks.

Occupational updates

When Big Business Daddy isn’t making John Oliver miserable, it’s doing its best to screw up the comic book company that it doesn’t care to own. In addition to throwing local comic shops into chaos, it’s created a good deal of work for me, given that DC Comics’ split with Diamond broke my Fresh Comics data ingestion pipeline. I’ve started to get comments from users complaining that the DC data doesn’t go as far into the future as Marvel and others, and over the weekend, I managed to get a “fix” in place that allows me to pull in 6 weeks of future release data for my DC fans. You can credit Spider-Man’s new robot for saving the Justice League. (And I’m not saying more than that!)

In client work, the past week has been one long exercise in “crossing the streams” of several formerly separate strands of project work, combining my constraint-based assessment system with passive data collection with automated SMS data collection on behalf of an academic client in Spain doing social science research on domestic violence in that country. Should be interesting to read what the project ultimately uncovers.

Interesting reads from the week

When Ramjets Ruled Science Fiction (Tor)

How Microsoft built its folding Android phone: From Surface Mini to Surface Duo (The Verge)

The Winamp Skin Museum lets you relive the wonderful chaos of late-’90s computing (The Verge)

Directors of Synchronic Ask You to Please Not Go See Their Movie (io9)

Mills' unlikely journey culminates in no-hitter (MLB)

On the Question of Current and Future Lockdowns (Maudlin Economics)

AI ruined chess. Now it’s making the game beautiful again (Ars Technica)

Interesting watches from the week

What’s the most non-intuitive thing you’ve been dealing with this week, CMDRs?